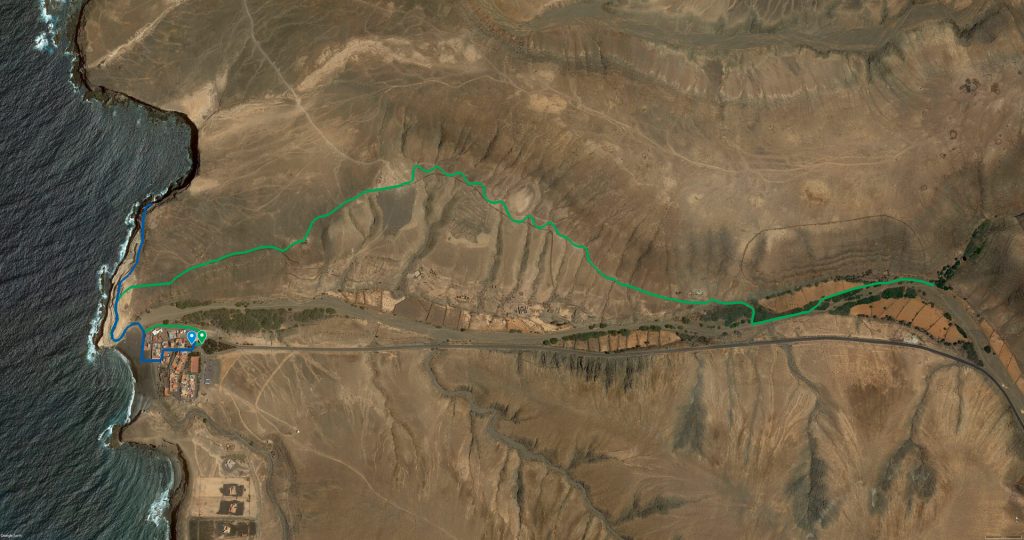

You are at the beginning of the green route between Ajuy and Madre del Agua, and the blue route through the Cuevas de Ajuy.

As you can see, both routes start from the same place, with the blue route running parallel to the green route as far as the entrance to the caves.

Starting with the blue route, cross the Barranco de Ajuy ravine to reach the Caves, a set of spectacular rock formations known not only for their beauty but also for their historical and cultural importance.

Their importance is such that these caves have been declared a Natural Area (Ajuy Natural Monument), the smallest protected area on the island. This is due to the fact that these caves contain the oldest geological materials not only on the island of Fuerteventura but in the whole of the Canary archipelago. We are therefore talking about formations between 100 and 150 million years old that have been shaped over the years by wind and sea erosion.

Inside, you can find various galleries and passages, with rock formations of different sizes and colours.

In addition to their natural beauty, the Ajuy caves have an important cultural history. The area is known to have been inhabited by the island’s ancient aborigines, the Mahos, who used the caves for shelter and worship.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, Ajuy was an important port on the island, as the Puerto de la Peña was used to export cereal, livestock, and lime to different parts of the islands.

With regard to lime, the Ajuy kilns are worth mentioning. The production of lime was a very important activity in Fuerteventura for many years, having its heyday between the 19th century and the end of the 20th century, as this material was used in construction and other industrial sectors.

The production of quicklime required caliche, a type of stone that served as a raw material and which was found in abundance on the island. The furnaces that began to be built on the island could be divided into two different types: lime kilns or domestic wood-fired furnaces (circular in shape and no more than 4 metres high), and industrial coal-fired furnaces (rectangular in shape and no more than 12 metres high).

In this regard, the charm of the Ajuy furnaces is that they do not belong to either of the two types mentioned; and although they reach a height of 12 metres, they are holes dug in the ground.

Continuing along the green route, it runs parallel to the blue route and separates from it at the top of the cliff to continue to the right and reach the wall that leads to La Aduana.

When you reach the Camino de Pájara, continue to the right until you reach a path on the right that will take you to the raspberries and old corrals. Follow this road to the Barranco de La Madre del Agua.

La Madre del Agua is a natural waterfall that emerges from the rock and flows into the sea, forming a natural freshwater pool. The water is crystal clear and fresh and is surrounded by vegetation of unparalleled beauty.

It is part of the Betancuria Rural Park, where you can find, among others, tarajales and dates. The latter were cultivated in the gullies that used the water here.

In addition to its natural beauty, Madre del Agua is also a place of great historical and cultural importance. It is believed that the ancient inhabitants of the island, the Mahos, used the waterfall as a place of worship and to perform water-related rituals.

The settlement of these ancient inhabitants is known as ‘Yacimiento Arqueológico Llano del Sombrero’, where we can find remains of aboriginal pottery and fauna in this well-preserved site.

If you want to return, follow the ravine again to get back to the small coastal village of Ajuy.

Ajuy was an important port of entry for expeditions to the island. In fact, the conqueror Jean de Béthencourt entered the island through Ajuy.

In addition, economic activity focused on agriculture and livestock farming, and it became an important centre of livestock and cereal production.